Own

a Piece of California

State History All

of our wood is

clear all heart

salvaged old growth

redwood. This salvaged

sunken redwood

has ax-shaved ends,

meaning it was

cut before the

late-1800s. Originally |

Fine

Craftsmen and WoodworkersWe

gladly interface

with owners, contractors,

architects, builders,

designers and/or

their agents to

provide you our

beautifully colored

salvaged redwood.

We know old growth

redwood and what

it can do. |

Brewery

Gulch Inn |

Myrtlewood

Available |

Customer

Reviews |

In

The News |

The

Salvage Story |

Green

Benefits and Durability

of Redwood |

Published in Sawmill & Woodlot Management Magazine, February 2007

A Woodlover's Dream Realized by Suzanne Rodriguez

|

|

Perched high on a rugged bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean and the mouth of the Big River, the entire 19th-century New England-style village of Mendocino, California, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The village's innate charm, combined with the region's breathtaking scenery and countless opportunities for outdoor adventure, has turned Mendocino into a prime weekend getaway for Northern Californians. In the last quarter-century, dozens of upscale, country-style inns and resorts have sprung up in and around town. Among the most highly rated of these is the Brewery Gulch Inn. Less than a mile south of town, nestled into 10 acres of forest and meadows above the sea, the 10-room inn has been heralded from its 2001 opening for many reasons, including its dramatic design, gourmet cuisine, sumptuous service, and jaw-dropping views. Mostly, though, it's been acclaimed for the stunning use of eco-salvaged virgin redwood, originally harvested around 150 years ago. And therein lies a tale... |

|

THE TALE

Back in 1850 a ship in the China trade ran aground near present-day Mendocino, leading to the discovery of the region's extensive virgin redwood forests. Before long an entrepreneurial San Francisco lumberman sailed up the coast with a 50,000-foot-per-day sawmill, set it up on the Big River, and went to work logging redwood trees.

With a life span ranging from 400 to 800 years, Sequoia sempevirens are found only along California's northern coast, from Monterey County to just beyond the Oregon border. The world's tallest tree, it can reach close to 400 feet, and attains up to a 23-foot diameter at the base. Redwood is valued not only for its beauty, but for its light weight and resistance to both fire and decay. Starting around 1852 and until about 1910, Mendocino supplied most of pioneering California's enormous demand for redwood lumber.

In those faraway days, logs arrived at sawmills by floating down a river. Most logging in the Mendocino area occurred during the summer, when the Big River was low. Logs were hauled to the river by mule or oxen. Twenty-seven splash dams were constructed on the river, and behind each dam was a "deck"—a collection of recently harvested logs. As the deck grew higher and heavier, logs at the bottom were eventually pushed down into the river's silt. In autumn, when the river swelled from rain, the dams would be dynamited open, allowing all the logs to rush downriver to the mill—except, of course, for those logs buried beneath the river's bottom. Year after year, more and more sinkers settled into the silt and mud. And there they remained—many for as long as one-and-a-half centuries—until a 20th-century entrepreneurial lumberman set out to find them.

ARKY CIANCUTTI—A TRUE WOOD FREAK

Arky Ciancutti, a self-described "wood freak," first heard about the logs in 1995. Trained as a physician, he had practiced medicine in the San Francisco Bay Area (among other things, he created and ran the emergency department at Marin General Hospital). In 1974 he left medicine to found the Learning Center, a consultancy that provides team-building advice to the healthcare community and a broad range of companies. He would also author a number of books, including the acclaimed Built on Trust: Gaining Competitive Advantage in Any Organization, which he coauthored with Thomas Steding.

One of Ciancutti's first Learning Center clients was located in Mendocino. As he traveled back and forth between the increasingly crowded Bay Area and the idyllic northern coast, he soon realized that he wanted to base himself in the small town. So in 1977 he purchased 10 acres of prime Mendocino land containing an early pioneer's farmhouse, which he gradually transformed into a cozy B&B (now closed).

Way in the back of his mind, Ciancutti played around with the idea of building a larger inn. For the next 18 years, in between professional and family obligations, he worked on obtaining permits and pondered various ideas for a design. But the project never seemed to coalesce. "For some reason I just couldn't get a clear idea of what I wanted it to look like," he says today.

That changed abruptly one night when Ciancutti wandered into a local bar and struck up a conversation with two burly, bearded brothers from Arkansas involved in major earthquake retrofitting of the Big River Bridge. Hitting it off, the three men tossed around stories for a few hours. Before leaving, the brothers passed on valuable information: Their industrial drills, they said, had hauled up red-colored wood shavings as deep as 38 feet below the river bottom.

If that was true, Ciancutti knew, the shavings were probably from first-growth redwood trees felled in the early days of Mendocino logging. And—just like that—he knew what kind of inn he wanted to build—if, that is, he could find and retrieve enough old-growth redwood logs.

FIRST THINGS FIRST

Before Ciancutti could actually begin, he needed a partner who knew the ropes and was willing to share knowledge. It would be no easy matter, after all, to find and retrieve these waterlogged giants. A steep learning curve would be involved, and more than a bit of courage: A river can be dangerous at any time, but working around bobbing multi-ton logs during tides and storms can be downright lethal. Three or four teams were already working the river in search of submerged logs. Ciancutti eased his way into this unusual and friendly community, working with a few different people until he finally selected his partner, Scott.

Together the two men constructed a simple pontoon barge made from two sealed road culverts filled with foam and covered by planks. Suspended between the pontoons was a chain with tongs on one end and a 5-ton mounted hand-winch on the other. At last, after gathering an assortment of other equipment, some of which had to be specially designed and constructed, they were finally ready to begin the search for "pumpkins" (prime timber).

Before too long the partners developed an effective routine. Using probes, they discovered a log settled deep in the river's mud. While Scott pried the log loose, breaking the vacuum beneath it with pressurized oxygen flowing through a hollow wand, Ciancutti applied muscle power to the winch one tooth at a time. No sandblasters or power shovels were ever used. By beginning at low tide, they took advantage of rising water to help ease the massive log loose. Ever so slowly the reluctant giant would rise from its long sleep.

Once free of the mud, the reclaimed log would be chained to the barge. The team then attached a 13-foot aluminum skiff behind the pontoon, fired up the skiff's outboard motor—the only powered mechanism used in the recovery process—and cruised on down the river. Arriving at the mouth at high tide, they dropped the log from its chains close to shore so that when the waters receded, the log would be left resting upon the beach. And thus each of Ciancutti's reclaimed redwood logs completed a journey that had been interrupted 150 years earlier.

|

||||||||

LEARNING ABOUT THE LOGS

Ciancutti took pleasure in learning how to date the logs, which—originally harvested between about 1850 and 1910—fell into three distinct time periods. A V-shape or "beaver-cut" meant that a log was felled with an axe between 1850 and 1876, when the labor- and time-saving raker-tooth saw was invented (in many beaver-cut logs they could see individual axe marks).

Logs cut with a saw and dragged to the river by mules or oxen were first shaved or edged around their circumference to prevent snagging. Such trees were cut between 1876 and the arrival of "steam donkeys" in 1895. All other retrieved logs were harvested after 1895.

Ciancutti was intrigued by another aspect of the retrieved logs: the initials they often bore. In the early days, he learned, logs were sold after felling but before being hauled to the river. Buyers came directly to the forest to buy in large lots; once purchased, buyers stamped their initials into each log's cut end. Only then were the logs brought to the river and stacked in a dam to await the autumn rains. Most would eventually be caught at the river's mouth, identified as to owner, milled, and then shipped by boat to San Francisco.

Ciancutti and Scott had many Huck-and-Jim adventures on the river. During one of the early trips, Ciancutti, who is not a good swimmer, fell overboard wearing steel-toed logger's boots that filled rapidly with water (he lived to regale others with this story). The pontoon wrecked a few times, with both aboard. Once, after a violent winter storm, they found an old logger's railroad axle brought up from the deep, and a few original logger's railroad ties hand-split from first growth redwood.

Soon after one of Ciancutti's logs was brought to the river's mouth and stranded on the beach, it would be picked up by a logging truck with hydraulic loading gear and taken "home" to his 10 acres. Waterlogged, weighing six or seven times its normal weight, some of the logs were so heavy that they had to be sawed in half before the logging truck could hoist and carry them. By mid-1996, nearly 30,000 board feet had been salvaged. Buying and trading brought about another 100,000 feet of first-growth redwood. At this point, the State of California began stepping into the process, making it difficult to freely reclaim wood. The time had come for Arky Ciancutti to move on. QUALITY SAWING AND DESIGNING THE INNAround this time he hired the best sawyer he could find to wield a Wood-Mizer on the logs now piled on his land. The sawyer kept the pieces as large as possible while retaining good vertical grain. "Everything was quartersawn, milled down to large cants, all clear, no knots," Ciancutti explained. "Tell your readers that we milled for quality, not quantity. They'll understand. During the sawing—which took nine months—Ciancutti and others worked the "green chain," taking the wood off the saw, sorting it, and storing it to dry. To move the wood, he enlisted the help of his Dodge power wagon truck equipped with a boom capable of 16 tons of lifting power. The wood was stickered with redwood spacers on level decks to ensure perfect air-drying. |

|

While waiting for the wood to dry fully—a process that would take three years—Ciancutti finalized plans for the inn. His design concepts were helped along by what might be the most impressive assortment of woodworkers living anywhere in the world today. That's thanks to master woodworker James Krenov, whose work is in museum collections worldwide. Back in 1981, Krenov started a one-year Fine Woodworking Program at College of the Redwoods in nearby Fort Bragg. Although Krenov retired some years ago, the program is still going strong. It continues to attract serious woodworkers from around the world, many of whom remain in the area after completing their studies.

"A lot of them had never seen the kind of wood I had," says Ciancutti. It wasn't only that the wood was reclaimed, but that is was so extraordinarily beautiful. After 150 years of resting in Big River's mineral-rich water, the tight-grained wood was infused with tones of burgundy, blond, red, purple, and honey-brown. It seemed to be lit from within.

"A lot of them had never seen the kind of wood I had," says Ciancutti. It wasn't only that the wood was reclaimed, but that is was so extraordinarily beautiful. After 150 years of resting in Big River's mineral-rich water, the tight-grained wood was infused with tones of burgundy, blond, red, purple, and honey-brown. It seemed to be lit from within.

The wood freaks helping Ciancutti refine his design hailed from different parts of the world, and each had a unique perspective, a singular taste. But one thing everyone agreed on was this: The wood should only be used to create something as beautiful as itself.

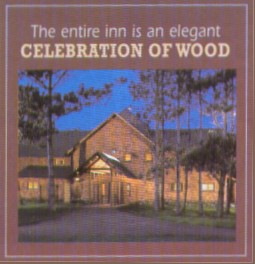

And the Craftsman-style Brewery Gulch Inn, with its 35-foot-high central ceiling and open feeling, succeeds. From the handcrafted entry door to the thick ceiling beams, the entire inn is an elegant celebration of wood. The Arts and Crafts-style furnishings throughout the public area reflect the architecture, with handsome tables of quartersawn oak and comfortable lunge chairs sharing space with a soaring glass-and-steel fireplace. Upstairs, all guest rooms feature the reclaimed redwood, including decks, vanities, paneling, rafters, and frames on windows and French doors. All told, about 16,000 board feet of Ciancutti's reclaimed wood was used to construct the inn. The wood is everywhere, sharing its beauty and open to admiration. At the same time, the building's masterful design ensures that the wood never intrudes. Thus, for some guests the reclaimed wood is merely a nice touch; for others it becomes a central focus, awakening primeval and even spiritual feelings. "For me," says Ciancutti, "the old growth wood is almost sacred. I feel the same way about the people who were on this land before us. The salvaging operation seemed to bring both worlds together: respect for the people who founded this area, and respect for the old trees. It's been a wonderful experience." |

|

Author, Suzanne Rodriguez tackles a wide variety of topics in her writing. She lives in Sonoma, California, and is currently at work on her fourth book. |

|

|

|

|